For more information about our hunting safaris, don’t hesitate to reach out and contact us!

A First Impala Hunt

by Mike Cramer

(Brooklyn, NY)

Epic poetry about kings and gods and the history of a people came only after people had learned to tell the stories of the hunt. They are our oldest tales, and from the dawn of time until today the story has been an integral part of the hunting experience.

In today's world, one wherein we can buy as much food as we want at Safeway and even order game off the Internet, the hunt story is as important a reason why people hunt as is the meat — maybe more so.

It is certainly more important than the taking of a trophy. The taking of a trophy is meaningless without the story of how the trophy was taken, and when the trophy is missed the story of "the one that got away" remains.

Hunting stories are the whole purpose behind all those hunting shows on television and most of the stories in any hunting magazine (well, that and selling us stuff we probably don't really need). The telling of the tale — the sharing of the story — is very much like the sharing of the meat from the hunt, and it lasts longer.

When the meat is gone we will have the story for as long as we are alive to tell it. Like food, stories bring people together. They are how hunters share the hunt with everyone else.

This is not my story, and to understand it significance you have to understand how I came to know it.

It was at an event in Western Pennsylvania called the "Pennsic War", a mock war and medieval festival held every August by the Society for Creative Anachronism, in which 10,000 people get together for what is essentially a two-week medieval theme party. They are there for four purposes: the mock battles, the parties, the classes on medieval culture and history, and to shop. A few of these activities even involve hunting. They often have demonstrations of lure coursing, where sight hounds chase a lure around a field. They might have classes on falconry or even stag hunting. There will be archery. And among the things you can buy from the hundreds of merchants in attendance are implements of hunting: hunting swords, boar spears, long bows, crossbows. Mongol-style recurve bows and even, from one merchant, atl atl.

Oh, yes... and books. This is a very bookish group.

I was working for one of the book merchants when I met the girl. She was young, in her twenties, with short blonde hair wearing a plain blue t-tunic. She was browsing all the tables (our shop was in a large tent with three other book merchants) looking for something in particular. Not much of what she saw seemed to interest her. Finally she came up to me and said "Do you have any books about medieval hunting?"

Now this was a question I had been waiting for for two years. You see, my interest in hunting comes mostly from an interest in medieval hunting. It was one more thing on a list of things about the middle ages that I had been drawn to study. I myself was not a hunter. My grandfather was a very active hunter, as was my great grandfather, but my dad took me hunting exactly once.

It was a pheasant hunt in California. I got off one shot and I missed. It was a good thing, because it was a hen. But I didn't realize that. To me it wasn't even a bird. It was just an explosion of grass and feathers that erupted from below my feet as I stepped on what looked like an ordinary clump of grass, a flurry of wings that had almost knocked me onto my butt and then flown away as I shot in its vague direction, far too rattled to hit anything. That's the story of my first hunt.

At the time I met the girl I hadn't really been hunting since. Well... OK. Once I had gone on a falconry hunt. We didn't get anything that time either, but it's a funny story. But studying Gaston Phoebus had led to an interest in hunting in general, and I moved from there to reading Teddy Roosevelt and Hemingway and thence to watching hunting shows on TV and reading magazines before I went out and got my license last year.

But back to the girl. She asked me about hunting books and I asked her why she was interested. She told me that she had recently gone on her first hunt and "had the bug", and she wanted to know as much about hunting as she could learn. I pointed her to another merchant who had copy of the Hackberry Press book The Hunting Book of Gaston Phoebus, which is not Phoebus’ book but a collection of hunting scenes from the manuscript in the Bibliotheque Nationale. Then I showed her our copy of John Cummins' excellent study The Hound and the Hawk: The Art of Medieval Hunting. The antique book merchant had a facsimile of Gaston Pheobus’ book, with a translation, but that was $300. I mentioned that there would be hound coursing and that there was a group in the SCA dedicated to studying the hunt, and that one of them would be teaching a general class on medieval hunting. We talked for a good half an hour about books and classes and other sources she could look at. She bought the copy of Cummins'. Then she turned to go.

"Wait a minute," I said.

"What?"

"You haven't told me your story yet. Tell me about your hunt."

She broke into a broad grin. She became very excited. And this is the story she told:

Her father was a big game hunter. He hunted all over North America and had been to Africa a couple of times. Recently he and a hunting buddy had booked a hunting trip to Africa but, at the last minute, his friend had had to cancel. The man had asked his daughter if she wanted to go instead. The flight, the hunt, everything was already booked and paid for.

The girl had never been hunting. She'd never really had an interest. She had only rarely fired a gun. But it was a chance to spend some time with her father and get a free trip to Africa, so she'd gone along.

Her father was there for Kudu. Every day he and one of the PHs would jump into a beat-up old land rover and trundle out across the plains in search of the gray ghost. When she first got there she had decided that, if she was going to hunt anything, it would be Impala, the "Whitetail of Africa".

She got some practice with a loaner gun and one of the guides showed her how to sight it in. Then the next day they put her in another Land Rover and drove out.

It was a simple setup, really. They found a watering hole and stationed themselves with the breeze in their faces about a hundred yards away. Soon some Impala stepped out of the brush and began to drink. The PH pointed out a nice sized male with decent horns and told her that this was the one. She was shaking. The buck was beautiful. She leaned in to the butt of the rifle, centered the cross hairs, and pulled the trigger. The Impala went straight down.

She arrived back at camp first, her dad having been farther out on his hunt. When he got back he said "How was your day?"

"Oh," she said, "pretty good." And then she showed him her buck. He was so proud! He was smiling from ear to ear. Some of the men helped her dress her Impala and then they butchered it and cooked it up for that night's dinner. Her Impala fed the whole camp! At one point one of the PHs handed her a plate with two deep-fried chunks of meat.

"What’s this?" she asked.

"The testicles," he said matter-of-factly. "It’s your first kill. You’re supposed to eat them."

She smiled and wolfed them down. Everybody laughed and congratulated her. He had been playing a trick on her. They weren't really the Impala's testicles, but she didn't care. If eating testicles was what it took for her to become a hunter she was happy to do it. The best part, she had said, was seeing the pride in her father's face.

After she finished I thanked her, and I realized at that moment that I had become part of her hunt. By sharing her hunt and her excitement with me she had made me a part of it, just as if she'd given me some of the meat. She had shared the fruits of her labor with me, and I... was honored. That was when I realized how important hunting stories are.

We talked about her next step, taking a hunter-safety course and getting her license.

She was from New Jersey, and I had taken the gun portion of the Jersey course, so I told her what to expect and wished her well.

I haven't seen her since, but as I sat in my own hunter safety course in the basement of St. Spyridon’s Church in New York City, I often though of her and her Impala.

Now, I've got a couple of my own hunting stories to share.

But those will wait for another day.

Mike Cramer

Comments for A First Impala Hunt

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

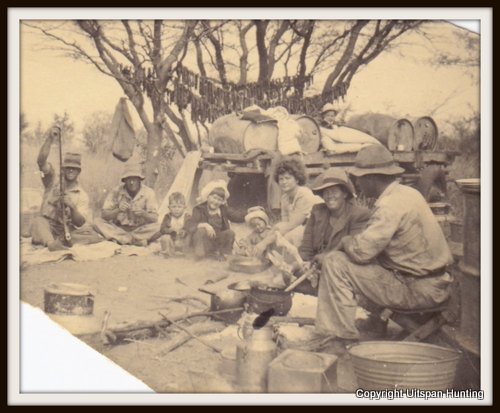

Meaning of "Uitspan"

'Uitspan' is an Afrikaans word that means place of rest.

When the Boer settlers moved inland in Southern Africa in the 1800's, they used ox carts. When they found a spot with game, water and green grass, they arranged their ox carts into a circular laager for protection against wild animals and stopped for a rest.

They referred to such an action of relaxation for man and beast, as Uitspan.

(Picture above of our ancestors.)

Did you know? Greater Southern Kudus are famous for their ability to jump high fences. A 2 m (6.56 ft) fence is easily jumped while a 3 m (9.84 ft) high fence is jumped spontaneously. These strong jumpers are known to jump up to 3.5 m (11.48 ft) under stress. |

Did you know? Some animals have one sense more than man!The flehmen response is a particular type of curling of the upper lip in ungulates, felids and many other mammals. This action facilitates the transfer of pheromones and other scents into the vomeronasal organ, also called the Jacobson's Organ. Some animals have one sense more than man!The flehmen response is a particular type of curling of the upper lip in ungulates, felids and many other mammals. This action facilitates the transfer of pheromones and other scents into the vomeronasal organ, also called the Jacobson's Organ.This behavior allows animals to detect scents (for example from urine) of other members of their species or clues to the presence of prey. Flehming allows the animals to determine several factors, including the presence or absence of estrus, the physiological state of the animal, and how long ago the animal passed by. This particular response is recognizable in males when smelling the urine of a females in heat. |