For more information about our hunting safaris, don’t hesitate to reach out and contact us!

Sea-ah'bra

by John deWeber

(Blaine, WA, USA)

We were riding in an old 70's vintage Land Rover, bumping up a mountain road in search of Hartmann's Mountain Zebra, deep in the heart of Namibia, Africa. Martin, a Namibian native, is the number one tracker for Frank Heger, my PH. This was day number nine of my ten day hunting safari and the clock was ticking. Martin said he "smelled" Zebra. Who was I to argue?

I had been dreaming of an African hunting safari for years. It's something that if you don't make happen, it never will. Like smoke in the wind, your dreams float away and disappear forever. Over the years, I have checked on numerous African hunting operations, but just never put it together. There always seemed to be some "good" reason why I couldn't go right then.

A little over a year ago, my longtime hunting friend, Gale Palmer, met Terry, a hunting consultant at the Big Horn Show in Spokane, Washington and we decided to "make" it happen. We dropped a grand into his pocket and locked ourselves in. There was no turning back at this point.

For over a year, we planned and dreamed of our big adventure. Missing this part of a hunt would be like skipping the courtship before marriage. Never a week went by without our talking about this hunt. We loaded bullets, shot our rifles, loaded more bullets, bought clothes, assembled our gear and packed and unpacked our bags innumerable times. It was like a never-ending Christmas Eve... two old men acting like kids looking over the banister at presents gathering under a Christmas tree.

And now I felt my bones being shaken apart as we inched our way up this primitive African road, if it could be called a road. We had covered this same ground three days earlier and I had missed what I hoped would not be the only shot I would get at a zebra. Call it "Zebra fever".

The Hartman's Mountain Zebra (Equus zebra hartmannae) is indigenous to parts of South Africa, South-western Angola and Namibia and lives in a dry, stony, mountainous terrain. They run in small intimate herds of five to fifteen animals, with a lead mare and a dominant stallion. My hunting guide was adamant that we would not take either of these important animals. Contrary to what so many people think, hunting the Mountain Zebra is a challenging and exciting adventure.

OK, are the stripes black on white or white on black? In contrast to the Burchell's Zebra of the plains, it appears that the stripes on a Mountain Zebra are actually black on white. But who cares? I really wanted one of these trophies. They are a spectacular animal and a formidable challenge to hunt.

Shortly after Martin's announcement that he "smelled" Zebra, we spotted a small herd high on the mountain ahead of us. The Land Rover ground to a halt and the engine died. All eyes (binoculars) were focused on this herd. We made out seven animals that were standing in the shade of small trees, at over 600 yards. A few minutes later, they just vanished from the earth. Frank later told me they had been tipped off to danger by a nearby troop of Baboons.

Frank bailed out of the Land Rover and told me to grab my rifle, chamber a round and put it on safety. He and Martin squeezed me in between and we dashed off after Zebra. We sneaked up over the crest and spotted those black and white stripes at about twelve hundred miles, give or take a couple. How in the world did those animals cover that much ground in that short of time? Frank read my mind and whispered that it was a different herd and the ones we were after were just up ahead.

We watched as they crested the next ridge and disappeared. I guess to Frank, that was the green flag. This was NOT the Kentucky Derby and NOT the Indy 500, but you would never have known that by the way Frank hit the starting gates. His legs were churning like an old cream separator as we did the 400 yard dash down into the valley and up the far side. I was holding my Browning Stainless Stalker as low as possible to keep the sun from shining off the silver barrel. Keeping up with this Lotus powered PH was like chasing a hydroplane with a rowboat. Thank goodness I had worked out on my treadmill for several months in preparation for this hunt.

Every time I dropped back four or more steps, Martin gave me a jab from behind. To make matters worse, the long grass concealed the softball and basketball size boulders we were zigzagging through and I spent most of my time just trying to stay vertical. This little sprint was turning into a quarter mile run. It was a balmy 90 degrees so I had a copious supply of sweat rolling down my back and dripping down my face into my eyes. I wanted to ask Frank if we were having fun yet but I couldn't catch him.

He slowed to a modest fifteen or twenty miles per hour as we neared the crest. My breath was coming in heaving gasps at this 4500 foot elevation, as I live at just above sea level. Someone forgot to tell me that Africa has a limited oxygen supply. I could see the joy on Frank's face as he looked back to see if I was still alive. I think he got a little perverted kick out of trying to wear me out. We had developed a great relationship by this time and he was enjoying my discomfort, but at the same time, doing everything he could to make this stalk successful.

We slowly eased over the top and looked down into the next valley. I don't know how these guys see game so quickly, but Frank and Martin immediately spotted the Zebra. They were about 250 yards below and moving around in the shade of trees again.

Now here's where the fun began. Instead of seeing how fast we could go, he now wanted us to do the duck walk. Imagine having your legs burning from sprinting cross country and then squatting low enough to do the limbo. I think this guy is a masochist. But just a few short minutes later, he pulled up behind a bush and focused his Leica rangefinder on the herd. He whispered, "One hundred and ninety yards" and turned to set up the Stony Point shooting sticks. Thank goodness he had given us a crash course on how to shoot over a stick.

It was completely different from what I was used to. When shooting from the kneeling position, I was used to raising my left knee and resting over it. Frank had instructed us to raise the right knee, place our right elbow on that knee, the rifle stock on the shooting sick and our left hand on top of our scope. This created a very solid triangle from which to shoot. Now, if you think assuming that position while peering through sweat-filled eyes at your trophy is easy, think again. I had to mentally work myself into position. I got ready and looked through my Leopold scope: branches; lots of branches between me and the Zebra; a plethora of branches. I was sure those branches had grown in this very spot for this very moment.

I whispered to Frank that I couldn't shoot. He said, "If you can't shoot, then move to where you can... and get it done soon". Oh, that wasn't too much pressure... I slid the shooting stick to the right and back to the left and then back to the right. There it was - a small hole I thought I could slip a shot through.

I took a deep breath, held the rifle as steady as possible after running a recent steeple-chase, and settled the crosshairs on the chevron, where the front leg attaches to the body.

Time stood still. I didn't want to miss this chance. I don't remember squeezing the trigger and hardly remember the recoil, but I clearly heard the "whuump" of my 250 grain Nosler Partition as it impacted flesh.

The herd erupted into a chaotic scramble. I watched through the scope as "my" zebra turned and galloped away. "Fall", I urged, "fall". But like the Energizer Bunny, it just kept going and was soon enveloped by the green flora of the African hillside. I turned to Frank and told him I thought it was a good shot. Maybe I was just trying to reassure myself.

We slowly (thank goodness Frank finally came to his senses) picked our way down into the valley to where the animals had been milling about. It seemed like forever getting there, but we certainly knew we had arrived by the splattering of blood on the grass and rocks. It wasn't a hard trail to follow and we moved slowly in the direction the Zebra had fled. Martin turned the corner and said, "Sea-ah'bra". Oh, I loved the sound of that word! There it lay, barely 50 yards from where it had been hit.

What a spectacular animal! I was filled with emotion. I love to be successful, but I always have a feeling of remorse as I stand over my fallen quarry. I must keep in perspective that we are providing a service to the herd through selective management.

Frank turned and shook my hand. Martin gave me a high five. I breathed a sigh of relief.

I had just completed my African "trifecta" of a gemsbok, a kudu and a zebra.

The sunset that evening had never been so beautiful.

I can't say enough about the quality experience I had. The accommodations were first class, the food never quit coming and the hunting was the essence of fair chase. Frank and Gudrun went out of their way to provide a true African hunting adventure.

John deWeber

Comments for Sea-ah'bra

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

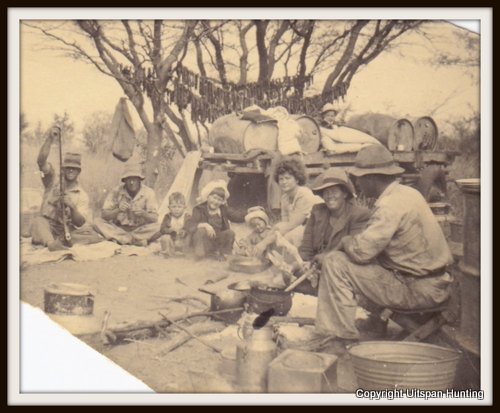

Meaning of "Uitspan"

'Uitspan' is an Afrikaans word that means place of rest.

When the Boer settlers moved inland in Southern Africa in the 1800's, they used ox carts. When they found a spot with game, water and green grass, they arranged their ox carts into a circular laager for protection against wild animals and stopped for a rest.

They referred to such an action of relaxation for man and beast, as Uitspan.

(Picture above of our ancestors.)

Did you know? Greater Southern Kudus are famous for their ability to jump high fences. A 2 m (6.56 ft) fence is easily jumped while a 3 m (9.84 ft) high fence is jumped spontaneously. These strong jumpers are known to jump up to 3.5 m (11.48 ft) under stress. |

to read about my experience...

Did you know? Some animals have one sense more than man!The flehmen response is a particular type of curling of the upper lip in ungulates, felids and many other mammals. This action facilitates the transfer of pheromones and other scents into the vomeronasal organ, also called the Jacobson's Organ. Some animals have one sense more than man!The flehmen response is a particular type of curling of the upper lip in ungulates, felids and many other mammals. This action facilitates the transfer of pheromones and other scents into the vomeronasal organ, also called the Jacobson's Organ.This behavior allows animals to detect scents (for example from urine) of other members of their species or clues to the presence of prey. Flehming allows the animals to determine several factors, including the presence or absence of estrus, the physiological state of the animal, and how long ago the animal passed by. This particular response is recognizable in males when smelling the urine of a females in heat. |